Wishing upon the stars

For centuries, people around the world have enjoyed fireworks to mark celebrations and as entertainment unto themselves. The advent of microsatellites, however, makes possible a more dramatic form of heavenly display: shooting stars that emit light while soaring through the mesosphere, about 60 to 80 km above our planet.

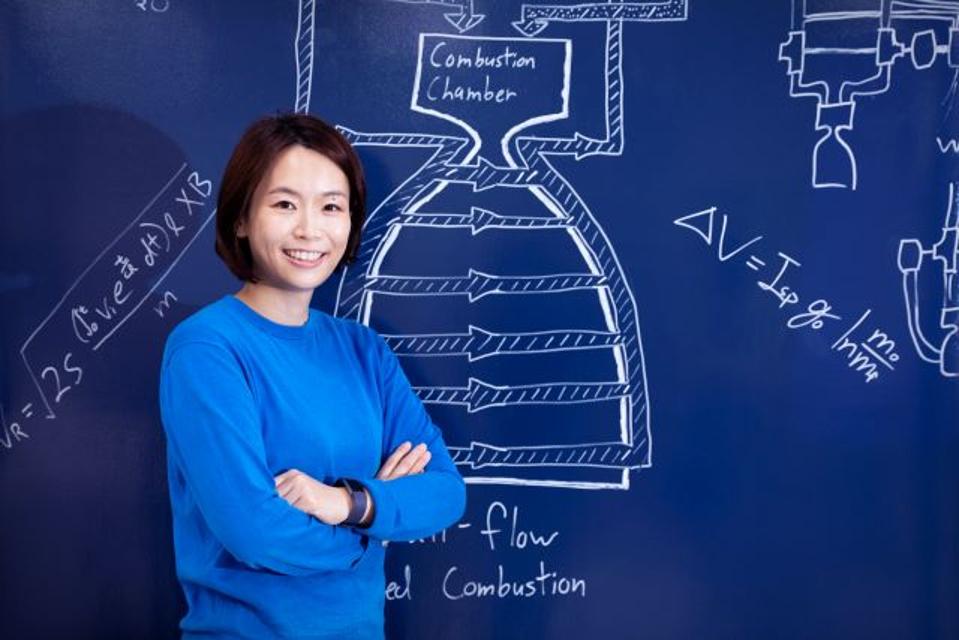

Lena Okajima, founder of space startup ALE, says man-made shooting stars will be “entertainment on an unprecedented scale.”

JAPAN BRANDVOICE

Sky Canvas is an aerospace entertainment project and it’s being developed by ALE, a space technology company established in 2011. Sky Canvas is the brainchild of scientist Lena Okajima, an astronomer and entrepreneur. Okajima has been fascinated by the cosmos since she read Stephen Hawking’s A Brief History of Time when she was a junior high school student. She grew up in Tottori Prefecture, which is reputed to have Japan’s best starry skies since the Milky Way is visible even in Tottori’s cities.

“I looked at the stars and often thought about the universe, wondering about black holes and cosmic background radiation,” says Okajima. “I also loved science, but when I went to university, I was surprised at how much time my professors, who were very talented, spent doing paperwork for grant applications.”

After she earned a PhD in astronomy at the University of Tokyo, Okajima decided to study business. She worked at Goldman Sachs for a year, and in 2009 began fundamental research on an idea that came to her when she had seen the Leonids meteor shower: would it be possible to recreate such shooting stars artificially?

ALE’s man-made shooting stars will be visible to everyone on the ground within 200 km.

JAPAN BRANDVOICE

Ten years later, ALE has about 30 staff and has raised some $26 million from Hong Kong-based Horizons Ventures and other investors. She’s now ready to make her dream come true. ALE has developed microsatellites that will release 1-centimeter particles from the upper atmosphere. These particles will ignite in the atmosphere.

While shooting through the sky, up to 20 particles will burn in different colors, and the display will be visible on the ground to everyone within an area measuring 200 km across. That’s much larger than the typical 10 km for fireworks, which exploded at an altitude of about 500 meters. These shooting stars can be deployed anywhere in the world.

“Our shooting stars can last longer than natural ones because they may be slower,” says Okajima. “It will be entertainment on an unprecedented scale.”

ALE is preparing for the first near-space test of its shooting stars with a rocket launch from New Zealand, whose space agency, part of the Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment, has certified the business on safety and legal grounds. Meanwhile, ALE is also developing another business: gathering information around the mesosphere, a region that is difficult to observe and about which there is little data. The data could be used to learn more about climate change, weather forecasting and other phenomena. ALE aims to sell such data to public- and private-sector clients.

It’s also working with the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA) on a satellite tether system to mitigate the growing problem of space debris. It would connect with small satellites that have reached the end of their useful lives and nudge them into the atmosphere, where they can burn up harmlessly. Space agencies, theme parks, cruise lines and large-scale event organizers are just some of the partners that ALE wants to work with.

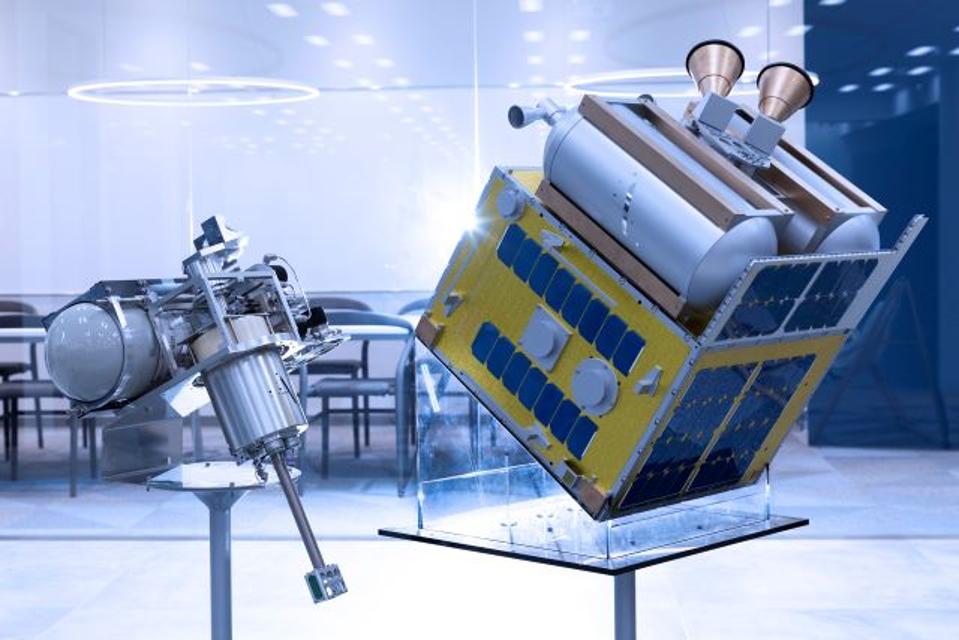

ALE’s microsatellite will orbit 400 km above the Earth, emitting man-made shooting stars and gathering data on the mesosphere.

JAPAN BRANDVOICE

“My motivation in doing this is that we can contribute to science itself without using public funds,” says Okajima. “One of our unique points is that we’re a private company pushing the frontiers of science.”

To the moon and beyond

While ALE aims to go to the edge of space, ispace is going all the way to the moon. It’s another Tokyo startup that wants to create new industries in space. It believes that by 2040, about 1,000 people will be living in a colony on the moon, with roughly 10,000 visiting every year. That’s why it’s developing a lunar transport and exploration platform called HAKUTO-R. It has already completed construction of a compact lunar rover and is working to finish the design of a lunar lander.

“We want to build a transport service to the moon, use its water, and build a gas station in space,” says Takeshi Hakamada, founder and CEO of ispace.

JAPAN BRANDVOICE

Takeshi Hakamada, founder and CEO of ispace, has been fascinated with space since he was young. Like many kids, he was inspired by spaceships he saw in science fiction films and programs and dreamed of designing his own spacecraft.

But unlike other kids, Hakamada didn’t put his dreams on the shelf and forget them. He studied engineering at universities in Japan and in the United States—it was at Georgia Tech that he first heard about the $10 million Ansari XPRIZE for reusable spacecraft launched by a non-governmental organization. Scalable Composites won that award, but Hakamada saw similar competitions as an opportunity to accelerate the private-sector development of space. In 2010 he decided to launch Team HAKUTO to vie for the Google Lunar XPRIZE, a $30 million competition for a privately funded organization to land a robot on the moon.

“I’d like to see a world in which cool spaceships are flying around,” says Hakamada. “It’s my genuine boyhood dream. To create that world, we need people in space. I want to help set the stage for that.”

While no team managed to claim the prize, HAKUTO was one of the five finalists. Thanks to the component expertise of its Japanese supply chain, it developed the world’s smallest planetary rover. With the experience and support it had accumulated, HAKUTO was established as ispace, and it’s now aiming to start the world’s first commercial lunar exploration program with two missions launching in 2021 and 2022, which will launch on SpaceX’s Falcon 9 rocket. Following those, ispace plans to establish a low-cost payload delivery system for the moon, where it will map water resources and surface features; this data will be sold to clients. Beyond that, it hopes to build an industrial platform on the moon that will be powered by hydrogen and oxygen separated from lunar water.

An artist’s concept of a lunar lander that’s part of a commercial moon transport system planned by ispace.

JAPAN BRANDVOICE

The company can’t carry out its vision alone. Like a racecar driver, Hakamada sports an ispace jacket decorated with the logos of six corporate sponsors; his company has managed to raise over $94 million from investors including Innovation Network Corporation of Japan and the Development Bank of Japan. It’s also working with Massachusetts-based Draper Laboratory as a subcontractor for NASA’s Commercial Lunar Payload Services (CLPS) initiative, which will begin transporting science and technology payloads to the moon in 2021. The European Space Agency has chosen ispace to be part of its science team for PROSPECT, a mission to extract water on the moon. Still, ispace is looking to collaborate with more partners in Japan and overseas.

“Our vision is to expand the planet and expand the future,” says Hakamada. “We want to build a transport service to the moon, use its water, and build a gas station in space. That would enable us to be mobile in space. We want to improve the quality of life of people on Earth by making use of resources in space.”

To learn more about ALE, click here.

To learn more about ispace, click here.

Comments :